Monk's Vision Of A Holier Web Gaining Support

Bringing The Word Online

“Because the Web is so personalized, because you can reach the whole person through it, there's a real power of intimacy in it.”

— Br. Mary Aquinas Woodworth

Brother Aquinas on Christ in the Desert and nextScribe. 582 kb (wav) |

| Web Links |

| nextScribe |

“The Holy Spirit will certainly guide the Church in the long run, but it would be wonderful if we could get a jump on this technology now.”

— Abbot Philip, the Monastery of Christ in the Desert

Brother Aquinas on getting the Church online. 337 kb (wav) |

An example of Web artistry from the Monastery of Christ in the Desert. A monk there is now hoping to spread Christianity through the Web. (Monastery of Christ in the Desert) |

By Michael J. Martinez

ABCNEWS.com

|

Catholic monks created the first modern books, set up the first schools and helped spread literacy, all so people could read the Bible.

But lately, the Church has lost its vanguard position, and at least one Benedictine monk has turned to the modern equivalent of illuminated scripture to spread the word: the World Wide Web.

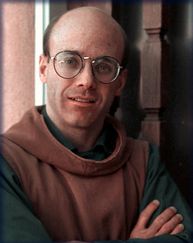

Brother Mary Aquinas Woodworth has given up his cloistered life at the Christ in the Desert Monastery in rural New Mexico to head up a new nonprofit corporation, nextScribe, dedicated to creating a place on the Web that promotes spirituality, understanding and peace.

The Power of

Intimate Communication

“Because the Web is so personalized,

because you can reach the whole person through it, there’s a real power of

intimacy in it,” says Brother Aquinas. “From a commercial standpoint, you

can use that intimacy to really very powerfully affect what the person is

going to buy. That’s fine, but if that’s all that this power is used for,

it’s going to be a terrible thing for people, on a human

level.”

Brother Mary Aquinas Woodworth (nextScribe)

“In the Middle Ages, you sat in front of a

book with a quill pen and illustrated,” says Abbot Philip, who runs the

monastery. “Today, the tools are different, but the spirituality of the

work is still there.”

The popularity of the

monastery’s pages led Brother Aquinas to the Vatican, where he helped

develop a site for the Holy See and the Pope. It also made him think about

other ways the church could reach out through the

Internet.

“The Vatican is not built for doing

the media,” Brother Aquinas says. “That’s just not its purpose in life.”

A New Vocation

Online

So about a year ago, Brother Aquinas left his

cloistered life, moved from the monastery to Santa Fe and set up

nextScribe. He’s now trying to raise money and recruit talented

programmers, artists and writers to begin work on a Catholic “portal”

site—a one-stop, subscriber-only Internet site featuring news, music,

video, games and other interactive hooks for all ages, all with a Catholic

message.

The fund-raising is a monumental task

in and of itself: Woodworth says he’ll probably need an investment of $5

million to start designing a site and eventually get it online. But he

doesn’t think that’s unrealistic.

“There are

70 million Catholics in the United States. Even assuming that only 10

percent of them are on the Internet, and that’s conservative, you still

have 7 million potential customers for this site,” Brother Aquinas says.

“That puts us No. 2 behind America Online.”

Brother Aquinas is actively recruiting HTML programmers, but the job may

not appeal to most Silicon Valley refugees. He expects his workers to live

by Catholic moral principles, pray at work, and make the job their

calling.

A Long, Hard

Road Ahead

Brother Aquinas has attracted some attention

within the church.

“Aquinas tends to be the

one voice in the wilderness,” says Francis X. Maier, chancellor of the

Archdiocese of Denver. “It’s hard to do what he wants to do on his own. He

loves the institutional Church, but he has a deep understanding of its

limitations. His work is really visionary.”

Maier and his boss, Archbishop Charles J. Chaput, understand the digital

medium better than most. The Archdiocese last month sponsored Newtech ’98,

a conference that attracted 50 bishops from around the world. In three

days, church leaders met with such digital-age luminaries as Neil Postman

and Esther Dyson, and discussed ways the church should approach new

technologies such as the Internet.

“In a

sense, the Web isn’t a very important issue at all when you look at

poverty and violence,” Maier says. “But in another sense, it’s very

important because it represents the new language that we can use to talk

about all these other issues.”

The Church’s

Digital Age

Most Catholic leaders in the field agree it’s

still a long way to go before the Web can be remade in God’s

image.

“In terms of the hierarchy—the bishops,

archbishops, cardinals—there’s still a lot of work. They now realize they

need to understand the technology and where it’s going,” Brother Aquinas

says. “But the conference was a milestone, and really set things going in

the right direction.”

Brother Aquinas admits

it’s still a long road, but his support is growing, both within and

outside of the church.

“I believe absolutely

in what he’s doing,” Abbot Philip says. “The Holy Spirit will certainly

guide the church in the long run, but it would be wonderful if we could

get a jump on this technology now. That’s his

vision.”

“I hope Brother Aquinas gets his

funding,” Maier says, “because I know it will bear fruit for the

Church.”

After all, didn’t John the Baptist

start out as a voice in the wilderness? ![]()